“If we let the tropes and set-pieces of our chosen genre define and limit our work in it, then we’ve surrendered the only real power we have as writers and artists… to CREATE! The best works of fiction don’t just affirm our beliefs and awareness, they expand them.”

“Trope” is a word that has seen a major spike in usage recently. Its strict definition is “a figure of speech” but it’s taken on a much larger scope of late, expanding to encompass “theme” or “set piece” or even “cliché” and is applied to film, television, literature, and any other storytelling medium. I prefer “genre archetype” but that’s just me.

But readers have a love-hate relationship with tropes. On the one hand, you read a particular genre because you can expect to find things in it that you enjoy. When I pick up a fantasy novel, I expect there to be magic in some form or other. By the same token, if the magic is the same magic from another book I’ve read by a different author, I’m disappointed. I want to see different expressions of the archetype, not a re-hash of something that’s already been explored.

I think writers that are new to the craft and still exploring their voice in it gravitate to tropes, even rely on them. This is a valuable exercise and gives the writer a chance to explore the elements of the genre that inspire them. I distinctly remember the first story I actually started writing was dripping with every cliché in the genre… dragons, bad-ass heroes, and magic straight out of the D&D Player’s Handbook (first edition, mind you… I’m old school).

I remember the pride I felt as I read my words, the same pride I imagine that’s felt by everyone who has chosen to try their hand at writing. Most of us didn’t have a tutor or mentor to guide us through our first efforts. We just wanted to express ourselves and add to the canon of a genre that had fired our imaginations.

But time and experience have revealed that I wasn’t adding anything new, and excitement turned to disappointment when I shared it with someone (other than my mother) and received a lukewarm response.

Tropes: Handle With Care

If we let the tropes and set-pieces of our chosen genre define and limit our work in it, then we’ve surrendered the only real power we have as writers and artists… to CREATE! The best works of fiction don’t just affirm our beliefs and awareness, they expand them. They explore the foundations of an archetypal theme or concept and reveal something new about it, something that adds to our perceptions and experience.

If I see a dragon on a book cover, I get a thrill of hope followed a split-second later by trepidation and skepticism. There have been so many stories about dragons that transported me through prose and plot, allowing me to surrender for a time to the notion that these were authentic creatures. And there have been other stories that just ride on the backs of others (pardon the pun) and left me bored and unsatisfied.

As a writer, you can’t (and shouldn’t) avoid the icons and archetypes of your chosen genre. The challenge is to understand their purpose in the context of your story. Understand that your readers don’t want something they’ve already read or experienced. Reading (for me, anyway) is an exploration, an adventure to someplace I haven’t been before. It needs to be vaguely familiar (so I feel comfortable) but with the promise of unseen treasures and unexpected twists that will lead to something I didn’t have before I started reading.

Examine the things you want to write about very closely. If it’s dragons, then what is it about those creatures that has caught your attention? Maybe it’s the destructive power that fascinates you. Maybe it’s their age and wisdom. Maybe it’s their connection to ancient and powerful magics. Do your dragons speak? Why? What is it about the capacity for speech that says “dragon” to you?

Don’t settle for “It’s just cool” as an answer. Yes, we know it’s cool. We read the genre, too. Why is it cool to YOU? Dig deeply and honestly and root out the real essence of your fascination. What you find there has real value to you as a writer because THAT’S what your story will be about. If you’re fascinated by a dragon’s apocalyptic destructive power, then your story will be about survival in the face of destruction or devastating loss/sacrifice or the cruelty of capricious fate to take that which is most dear to you.

Use the tropes as they are intended: as gateways to a new understanding of your world. These archetypes awaken passion and excitement in us for a reason and that reason is different for each of us. Don’t pander to me and try to use MY reason as YOUR writing tool. I’m interested in YOUR reason… that’s what will make your story a unique expression of your craft. I may not like where you go with it, but you will have added to the canon of a genre I love, and for that, I will heartily thank you.

Tropes can be great places to start thinking about a story.

And a bad place to stop.

Personally, I think you need to understand the tropes of the genre before you can really hope to tell a good story in that genre. I can’t tell you the number of hopefuls that have sent me their wonderful new stories that have punchline endings like “…and the man’s name was Adam.”

Honestly, I think I wrote one (or two) of those myself before I realized that — as you say — I wasn’t adding anything new. Retelling the story of Pocahontas in space might work, but you gotta make the story your own or it’s just a rip-off.

Myself, I start with the tropes I want to use and think about how I’m going to twist them. Not using them isn’t allowed, because without the tropes you have no hook to hang the plot on.

Examples:

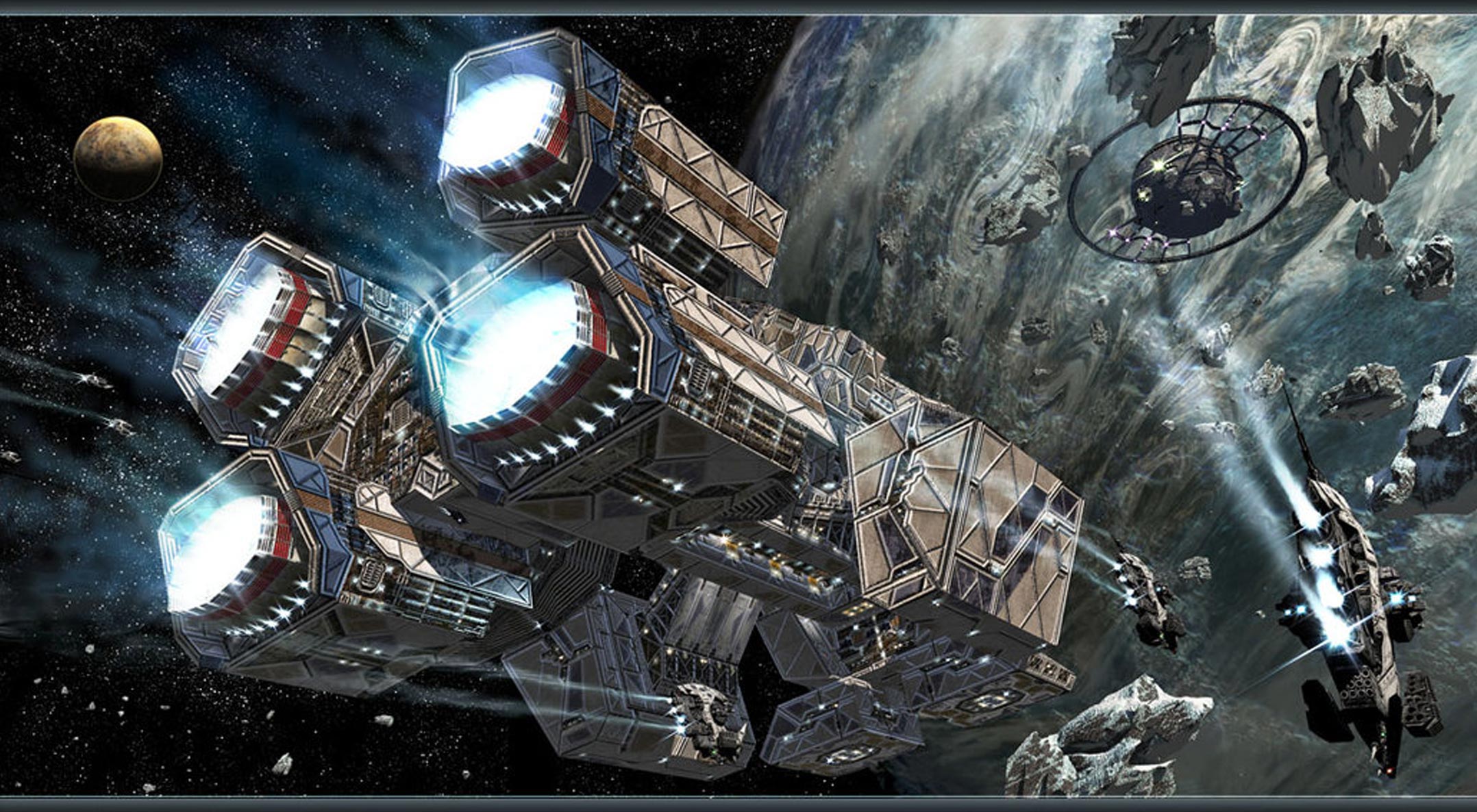

In my Solar Clipper series, the tropes of “space ships” and “interstellar travel” got merged with a classic “coming of age in a foreign culture” trope. I also set about trying to write stories about what the universe would look like if we sent out freighters instead of frigates and settled the stars with airlines instead of an air force. This was a direct response to the current market where everybook needs to save the universe every fifty pages and something has to blow up every twenty. A lot of people don’t like them, because they violate the first rule of space opera — they don’t have a sweeping arc of huge danger and massive catastrophe should our heroes fail — and they trample on some of those preconceived notions. On purpose.

In my fantasy work, I took the trope of “the young person leaves home and finds their magic power through puberty” and the “innocent saves the world from Great Evil” tropes and turned them upside down. A woman who is trying to get home finds her power as her body undergoes menopause. And she thinks she’s going mad. The only world she wants to save is the one inside her head.

I also think that a key to this idea is that you cannot write if you do not read. I’m not talking “a book a year” but something more like “a book a week or more” for at least a few years. In every genre there’s a body of work. If you don’t have a grounding in that body, you run the risk of confusing trope with cliche, of herding good words in to the same old flocks.

Thanks for your thoughts, Dave. Great things here.

“Tropes: A great place to start, a bad place to stop.” Perfect summary for the discussion. I appreciate the affirmations and observations, Nathan.

I agree completely regarding the essential nature of reading in this context, but let me ask you… what’s your opinion on the merits of other media (movies, podcasts, television) as alternate grounding material? To clarify, I agree you can’t learn to write effectively without reading (voraciously), but in the context of ideas and story development, can ANY storytelling medium serve as “foundational experience”?

I ask because I was going to pursue that line of reason (and may yet in a “ptII”) but found the waters a little muddy and I wasn’t sure of my footing.

Movies, TV, podcast, transmedia … all good places to look at storytelling. How does the story unfold? How did the director/writer make this character sympathetic? That one despicable? I’ve been watching “Lie To Me” lately on Netflix to see how they tell a very compelling story using an esoteric branch of behavioral science to explore the way people interact.

I think a lot of my written work has been influenced by film/TV. There are shows I’ve watched, just to see how they tell the story. The difficulty is that visual arts have tools that don’t translate well on the page.

Example: Jump cut.

The flash of a scene in full detail, cut to the next, cut to the next.

You can’t do that in prose because the essential characteristic (rapid scene change) can’t be accomplished in text. It takes longer to read ten words than it does to grok the jump cut.

BUT

That technique can inform a narrative’s pacing. What about the jump cut works? Why does the film-maker use it? What does it do for tension? For pacing? Now take that idea and see how you can adapt, adopt, or augment your writing with that new understanding about story telling.

As far as *tropes* go, I think non-text media have something to offer. American s/f fans know all about the various generations of Star Trek and Dr. Who, but few know of Blake 7 or Charlie Jade. There’s a rich vein of tropes to be mined — particularly in the international media.

References to “Blake 7” and “Charlie Jade” sent me running to Google and Wikipedia and for that I thank you (Charlie Jade in particular caught my imagination).

Your point regarding the translation from motion/sound media to text hits home particularly closely… my biggest challenge (and I think the challenge of many new writers) is resisting the impulse to write “cinematicly” (sic), describing every nuance to inform whatever action is unfolding. This, I have found, is “description”, not necessarily “writing”.

You’ve inspire me to write two new posts: “Let the story tell itself (Resisting the Cinematic Urge)”, and “How to Watch a Movie Like a Writer”.

Thanks, Nathan! 😀

Shirley, I have only read Running with Scissors ” but I found it fascinating. I tend to think no one gets to say for each of us what is our Truth. My siilbngs have taken offense to my upcoming memoir but have admitted that my experience of life in our family and theirs was different. Even as siilbngs, we don’t live in the same family. Did Burroughs get all the facts right? We as his readers have no way of knowing that. Could it still be his Truth even if some facts are inaccurate? I think, yes. Does his memoir still deserve attention? Definitely. Reading memoirs has given me tremendous insight into other families and helped me realize the Leave it to Beaver families are rare if not fairy tale. Thanks for the links to the NPR story.